As a child I spent a lot of time each summer in a canoe. So much so, that at 15 I was comfortable standing in a canoe and doing a complete 360 (a ‘test’ we had to do before heading out on a school canoe trip). The only formal learning about canoeing I ever got was on this day. The only thing I got out of it was how to do a j-stroke – the stroke the rear paddler uses to control the canoe. I’d never paddled from the back before, there wasn’t a need. Instead I had became an expert front paddler. You might be thinking expert? All you do is paddle? While this is true in open waters, in tighter spaces, shallow water, and near shore you are the eyes of the team: Can we squeak past that overhanging branch blocking the way? Is that rock under water too shallow to pass over? How will we get around this barricade? In short, you need to know when (and how) to help avoid obstacles and maneuver the canoe in tight spaces. What’s notable is that none of this ‘knowledge’ came from reading or formal instruction. It came from lived experience with an experienced canoer (i.e., dad) in behind.

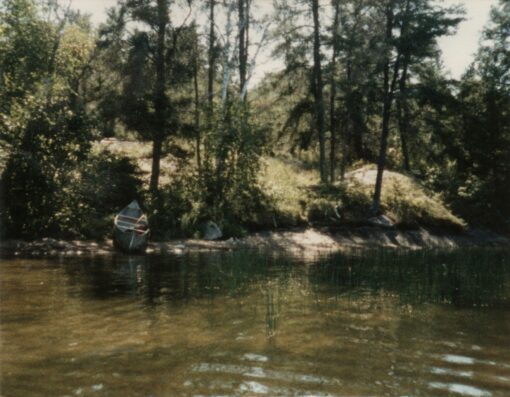

Today, I don’t get in a canoe as much as I’d like – maybe once every year if I’m lucky. One of my more recent trips was to Algonquin Provincial Park in Ontario, near where I was working on my PhD. This place was chosen because of its remoteness, its familiar topography, and its history with the Group of Seven. While this trip was special for those reasons, most of my canoeing is in familiar waters, on the lakes I grew up with.

Paddling a canoe is slow, which means you are able to fully experience the lake – instead of seeing it as an observer, you become part of the lake. It is from this perspective that you can enjoy some unique experiences, like seeing an eagle dive nearby to catch a fish that’s a little too big; spotting a reclusive common merganser leading her ducklings off in the distance; witnessing a group of pelicans working together in a line to drive fish (i.e., dinner) to shallow water; watching the awkward takeoff of a cormorant (aka crowduck); observing a loon preening itself right next to you; or even spotting a deer (or bear!) come to the water’s edge for a drink. If you’re up to the challenge, and explore a little off the ‘beaten path’ into the marshy fringes, you may even find otters, beavers, or a turtle or two. And this is just the surface – literally.

These experiences are the foundation of what it means to understanding a lake – of understanding the complex system that it is. Coming to have this depth of understanding is what knowing truly is. While this is not something that is quickly attained, moving towards this level of understanding is what all learning should be.

Leave a Reply