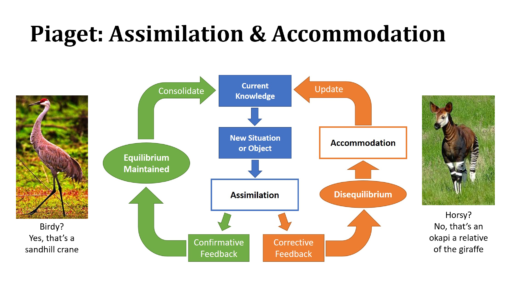

Cognitive presence, with its triggering event, exploration and integration, remind me of Jean Piaget’s concepts of assimilation and accommodation (which is a topic I cover in my courses). While Piaget focused on the cognitive processes of infants, it is highly unlikely that adults use altogether different processes. In fact, I take advantage of this when I demonstrate these concepts in class.

When students are first shown the green path in the above image and the pink colored bird, they have no difficulty adding that “birds other than flamingos can be pink”. This is easy and quick. However, when they are shown what looks like a horse-zebra hybrid, things begin to get interesting. Despite the animals appearance, okapi are in fact the only living relative of the giraffe. It takes students quite a bit of time to resolve this kind of situation. This reworking of what it means to be a horse, a zebra, and a giraffe takes a noticeable amount of time. Incidentally, both animals are endangered.

Another related concept is social psychologist Leon Festinger’s cognitive dissonance. Festinger found that people experience a mental conflict or tension when new information contradicts their beliefs or assumptions. This tension could be resolved in several different ways – most of which (e.g., reject, explain away, or avoid the new information) are incongruous with the goals of education. While some disciplines are unlikely to experience this phenomenon, when it comes to the social sciences, it is very likely that students will encounter new information that conflicts with their existing world-view. In these cases, only students who are willing to reconcile that their existing world-view needs updating will actual gain from the experience.

In short, for learning to be effective there needs to be a willingness to experience a sense of unease, disequilibrium, or cognitive dissonance from time to time. This is an uncomfortable place to be, but it is a fact of life that sometimes our understanding may be a little off or just plain wrong. The concept of cognitive presence seems to make the assumption that all triggering events will inexorably lead to positive exploration that redefines the learners understanding. But what if it doesn’t? What if instead learners proceed down some other, less uncomfortable path, that is not at all what we intended?

One Response

Douglas Alards-Tomalin

Very interesting ideas here – do you think the sense of discomfort people experience after corrective feedback might be a reaction by the organism (in this case people) to preserve the initial concept in order to avoid the energy costs of updating the schema?